100 Days of Chaos

From becoming entangled in a new bribery scandal to ramping up to another austerity budget, the new government has failed at every hurdle, struggling to articulate a coherent vision or direction.

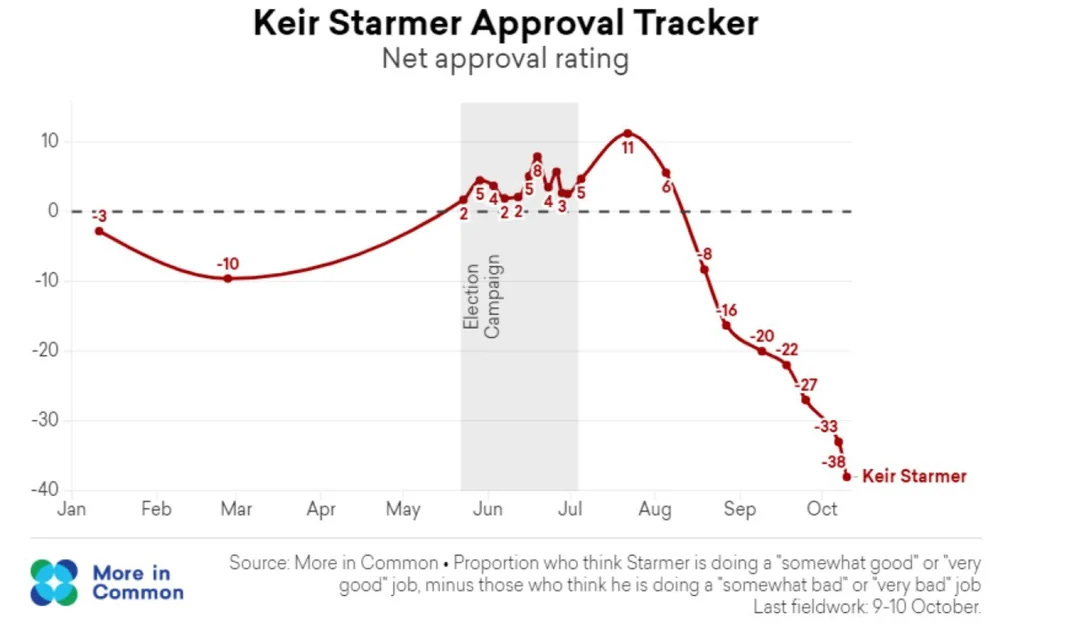

Everyone expects a new government to lose momentum over time. It’s inevitable. As the party changes gear from campaign mode and winds down all the adrenaline highs that conjures to governing in a restrained way, they’re no longer looked through with rose-tinted glasses but subjected to harsh scrutiny. Political honeymoons - a term referring to the brief swell in public support an incoming government receives as it takes office - usually last for several months until there reaches a point where voters become disillusioned when the bullish predictions and promises made on the campaign trail eventually collide with the harsh reality of cold statistics. Idealism gives way to pragmatism and the outsider becomes the establishment.

The steep collapse of this new Labour government is unprecedented, however. 100 days after winning the election, not even the most sanguine of Conservative supporters expected Labour’s support to crater as quickly or drastically as it has done. The party has fallen from 34% (an already low figure) to an average of 28% in the last opinion polls. When asked in a recent survey how they would rate the party’s accomplishments, 43% of voters said nothing Labour introduced so far had made any tangible difference to their living conditions, including 22% who voted for the party at the election. More voters now rate Rishi Sunak as a better prime minister than Keir Starmer.

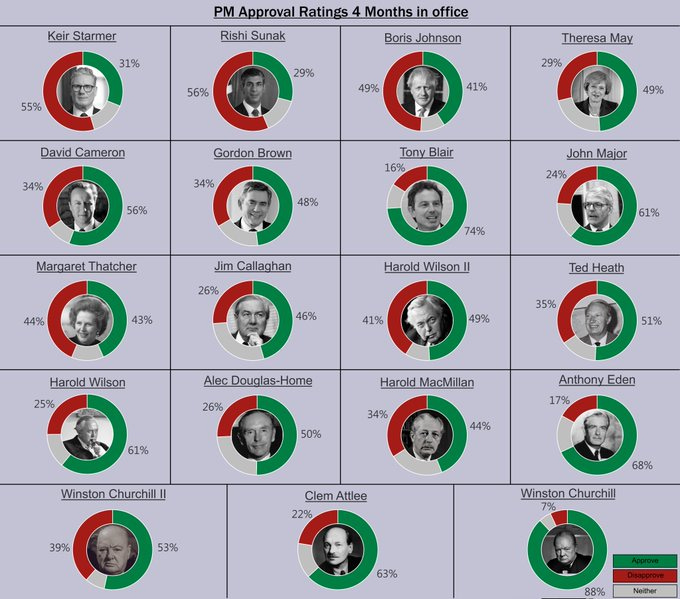

Chart showing the average approval rating for post-WW2 British PMs four months into office, courtesy of @RealLiv04.

Perhaps, some of it can be attributed to the severe polarisation politics has underwent in the social media age. With information readily available at the swipe of a finger, the electorate has never been more elastic and is now shows willingness to switch from one party to the next in a volatile manner, uncharacteristic of the UK political scene which once prided itself on its entrenched political affiliation . One only has to look at how well Reform, a party founded a few short years ago, is polling now, almost on the verge of eclipsing the two main establishment parties.

Labour, as Starmer wastes no opportunity talking about, inherited one of the most economically disastrous mandates since World War Two. Fixing it will be a herculean task. Keen to avoid the same mistakes as Tony Blair, who later admitted he wished he had done more early on, this Labour government got off to a hyperactive start after 14 years out in the cold. But along with all the big decisions, new legislation, foreign trips and attempts to set the political narrative, they have found themselves buffeted by headwinds: not just over donations, but also stories of internal rows at No 10.

The cash-for-clothes row, in which Keir Starmer, Angela Rayner and, to a lesser extent, Reeves have come under sustained fire for accepting gifts worth thousands of pounds from Labour peer Lord Waheed Alli, has been a low point for the newly elected government. But it’s less about the substance and more about what is symbolises. Most of Labour’s election campaign saw the party parallel itself with the Conservatives, notably when Starmer contrasted his career of national service as the Head of the Crown Prosecution Service with the lies and deceit of Conservative leaders. Senior party cadres vowed that, upon entry to government, they would reignite voters’ confidence in the political system by sweeping away the stench of corruption and nepotism.

What Labour needed to do was either present a cohesive vision for the future that excited people or to have a massive set of prepared policies with 'quick wins' to push through immediately if they were not going to be going for big structural change and, or, hope.

Instead, it seems like they had very little actual enthusiasm in the election and skated by being 'not the Tories' and the opponents blowing up, but that's a very flimsy footing public opinion wise leading into a government and needing to be in power. And if you ran on being the adults in the room and not on visionary reforms, then they needed to show that preparation to rule immediately, where it seems like they've trickled in bad news and unpopular policies and self-inflicted 'scandals' without any major positive aspects to point to.

The Labour Party can’t spend the last 14 years chastisting the Conservative Party for ushering in a period of austerity politics only to then turn around and repeat those same mistakes while in office and expect to be taken seriously. The mental gymnastics necessary to justify that hypocrisy

On the very first day, his government scrapped the Rwanda Scheme, which, despite all of its flaws, acted as a deterrent to migrants seeking entry on small boats. Since then, more than 13,000 migrants have crossed the channel in their first 100 days, the highest on record. Nothing concrete has been brought forward about ‘smashing’ the human trafficking gangs who funnel the migrants over or how the new Labour government hopes to coordinate with European allies. A few platitudes were thrown around to the media like scraps for starving dogs before the government promptly sidelined the issue.

Next, 1,700 prisoners were released ahead of schedule under an early release scheme intended to relieve overcrowding in prisons. 37 prisoners were let out by mistake, five of whom went missing and a significant proportion of those released early (57 so far) are back behind bars.

Labour has given away the Chagos Islands, a British overseas territory located in a contentious area of the world, to Mauritius, a Chinese ally. Now, British citizens are expected to pay for the privilege of giving away their own territory without consulting the Chagossian people. It doesn’t matter that the last government initiated the negotiations. Starmer had the opportunity to reverse the decision and choose not to. The blame ultimately falls upon his shoulders, not Cleverly.

Even if one can swipe these decisions away as headaches inflicted by the previous governments, it’s not as if the party brought the political stability they once promised. Chief of Staff Sue Gray was ousted after just a few months in the role. Seven Labour MPs have already lost the party whip and one Labour MP, Rosie Duffield, has quit the Labour Party to sit as an independent.

Starmer doesn’t seem fazed by all this and why should he be? The next election isn’t for another 5 years, enough time for the Labour Party to rehabilitate its image and claw back some of the voters who have deserted them in recent months. But, the biggest problem he may face is that, historically, incumbent governments tend to become more unpopular as time goes on. Only a few governments have buckled that trend.

The government’s parliamentary majority is already predicated on one of the most disproportional electoral results in British history, with 34% of the vote share translating to over 60% of the seats, not to mention that it was achieved on one of the lowest turnouts in decades. If the Conservatives and Reform strike an electoral pact or merge entirely, however, he may be faced with an insurmountable conservative opposition. At the end of the day, most British people are small-c conservatives. It’s no coincidence that higher turnout often corresponds to a larger conservative voting block (The Conservatives increased their vote share from 2010 to 2019 alongside an increasing turnout).

Starmer seems to be under the impression that just by changing the frontbenches of the government, giving Whitehall a fresh coat of paint and ‘reforming’ the public services, he will be able to reverse 40 years of constant decline.

Disregarding the fact that ‘reform’ is an ambiguous and vague concept whose precise definition varies from person to person, Starmer’s prescriptions amount to nothing more than papering over the cracks. As mentioned previously, the issue our country is facing is a question of structural malaise. Simply reconfiguring a department’s budget or adjusting its goals will not suffice. A bigger, more radical overhaul is needed.

Starmer is shaping up to be less like his idol Tony Blair and more like former French President Francois Hollande (2012 - 2017), a personally dull technocratic centre-left leader who manages to actually win an election against a corrupt and unpopular centre-right incumbent government before failing dismally in office, ending up as popular as smallpox.

Much like France, in the absence of a compelling vision that the country can rally behind, we may see the growth of extremist parties as people reject the establishment parties and look for a vessel to challenge the status quo. Last election already saw several independent candidates win constituencies with sizeable Muslim populations after campaigning on secretarian issues, predominantly the Israel-Palestine conflict. It’s not implausible to suggest that an organised, highly-disciplined Islamic party could find a foothold in the British parliamentary within the next decade.

Many of the decisions Starmer has taken since coming to office may fade into the background and be forgotten. After all, the media can just as easily move on to another topic. But they provide an illustration for the new government’s philosophy and how they seem to be governing recklessly because they feel immune thanks to their insurmountable parliamentary majority.

This is to say: one hundred days is a small snapshot in history, but the decisions can very well echo for years to come.