How To Fix The West's Declining Fertility Rates

For an issue this multifaceted, there is no easy solution. But flexible work cultures, pedestrian-friendly cities, and cheaper housing prices can go a long way in mitigating the crisis.

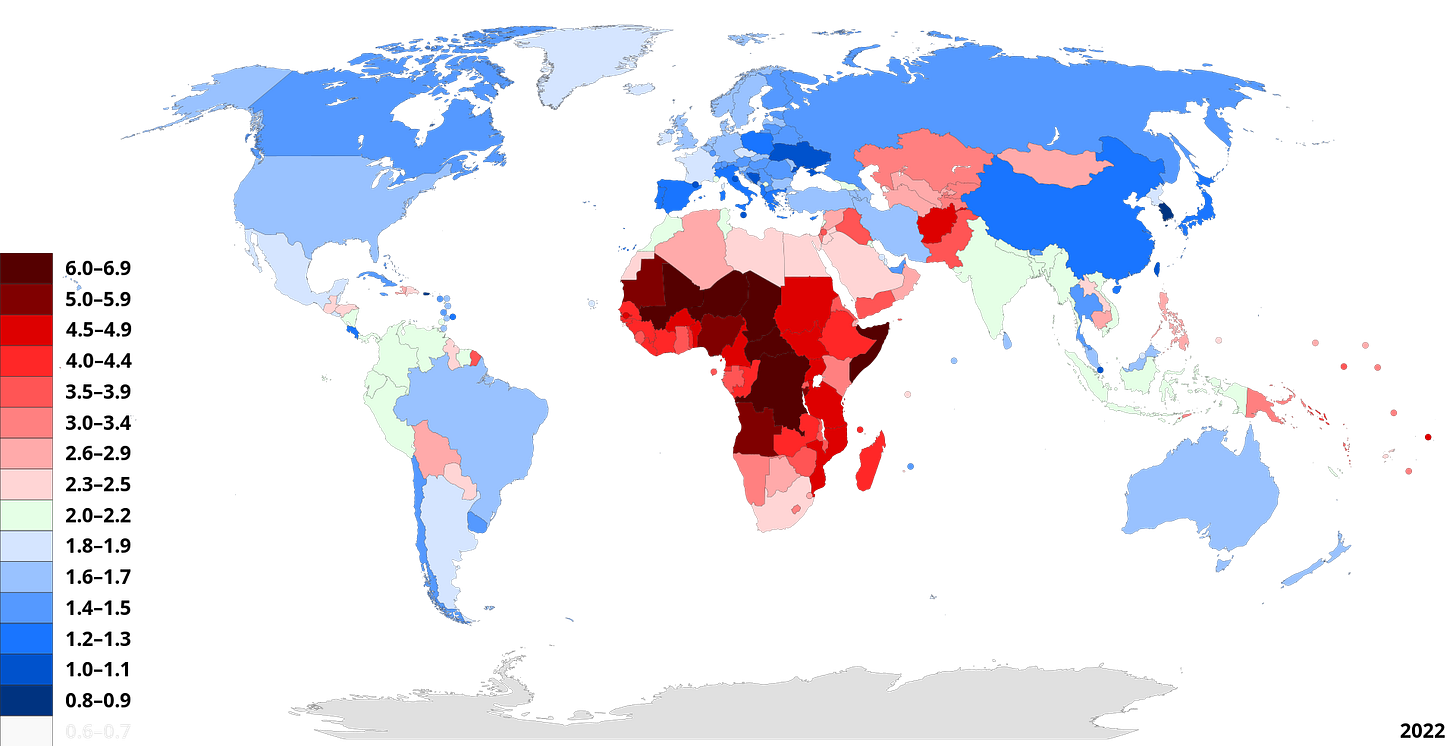

The feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s was a time of monumental change for European women. Across the continent, women gained the right to equal pay, were able to own credit cards, and could apply for mortgages in their own name. This paradigm shift naturally resulted in a drastic increase in women’s workforce participation rates. However, the inescapable sacrifices of a capitalist economy forced many of these women to choose between having children or pursuing a career. Many chose the later. Consequently, Europe’s fertility rates dropped substantially, and by 1990, all of the current EU member states had fertility rates below replacement levels.

Fears over lower fertility rates are usually dismissed by the media as right-wing scaremongering, but the demographic shifts that result from them can have an unprecedented impact on our societies when allowed to spiral out of control. Scholars are already predicting that these low fertility rates will cause instability within the European welfare system. Since welfare programs are financed by taxes on the working population, low fertility rates will either increase taxes for a region that is already one of the most highly taxed areas in the world, or incentivise governments to pursue austerity programmes as a way of stabilising public finances. None of these options are ideal.

One only has to look at the worsening demographic crisis in South East Asian countries like Japan and South Korea to see what awaits Europe if it doesn’t change course. With a rapidly ageing population, the pension and healthcare systems there have become a burden on public finances, strained further by the shortage in younger workers. Communities, once thriving, are now becoming ghost towns.

In 2001, McDonald and Kippen conducted a study in which they examined the labor supply of sixteen developed countries. They concluded that all of them could face labor supply shortages within the next forty years, noting that Europe was particularly susceptible to this. Although the size of Europe’s workforce is expanding, growth is slowest in European countries. This, coupled with their propensity for “very low” fertility rates, foreshadows trouble for Europe’s generous welfare system. Aside from encouraging mass immigration - which entails significant changes to Europe’s politics and culture - implementing natalist policies seems like the most viable solution to increase fertility rates.

Maternity/Paternity Leave

According to all major studies conducted on the issue, maternity leave was found to reduce, or even reverse, the rate of decline in fertility rates. Kalwij (2010) explains this phenomenon not as a conscious decision to have more children, but as a change in the average age at which women choose to give birth. He finds that paid maternity leave encourages women to have children earlier on in life. This effect is most pronounced among younger cohorts because as women age and progress their career, the opportunity cost associated with taking time off from a highly paid job discourages them from having children. From a biological perspective, having children earlier gives women the option to have more children later on in life.

This argument was strengthened by Geisler and Kreyenfeld, who argue that, while economic choices are an important factor, cultural norms regarding good parenting are more influential. Karu and Kasearu exemplified this argument with their survey of Estonian fathers. Many men chose not to take parental leave because they feared they would be insufficient parents, assuming, instead, that mothers would be better caregivers due to “natural instincts and a biological connection they develop with the child during pregnancy.” This reasoning makes it clear that perceived beliefs about parenting and gender norms are very important factors when making decisions about parental leave. A solution to this problem would be to prioritise paternal leave over gender neutral schemes since studies have shown that fathers are more likely to use paternity leave and fathers’ quotas than gender neutral parental leave as the stigma of taking time off work is less apparent due to its compulsory nature. The Nordic countries were able to maintain, or even increase their fertility rates partially because of their egalitarian attitudes and paternity leave policies which were implemented between 1991 and 1998.

Several months of leave may increase the father’s confidence in his parenting abilities. This will assuage fears about being an insufficient parent and challenge the widespread belief that mothers are instinctively better caregivers. As their confidence rises, men will feel comfortable with having more children. This will also have a positive impact on his partner. From the female’s perspective, the egalitarian distribution of housework makes it easier to pursue both a career and a family.

While maternity and paternity leave have been widely available in Europe for decades, most of these programmes have become undermined by government defunding and the benefits not keeping up to date with rates of inflation. This demonstates that not only do the programmes need to be strengthened, but they also have to be constantly updated to reflect the economic situation.

Flexible working culture

Another solution is to provide workers with more flexible working-hours, or to encourage businesses to include remote work within their programmes. In most countries, strict work cultures are in conflict with family life. Young couples are far less likely to have children if their work gets in their way and prevents them from spending quality time with them. If a significant portion of their day is going to be consumed by their work, some may be hesitant to sacrifice their free leisure time raising a family.

Shorter working hours not only makes it easier for couples to have children but it means that parents aren’t locked out of job opportunities when they return to the workforce after their leave of absence. And there are other ways to make work flexible without reducing hours. A study in 2017 showed that increased access to broadband in Germany correlated with higher birth rates in highly educated women. Working from home, women found they could spend more time with their children and thus they choose to have more. While not every profession will be able to delegate responsibilites remotely, those that can should.

By evolving the work culture in certain occupations from a strict, regimented timetable to a more flexible one, we can help young couples to tailor their schedule around their home life. Knowing they have that freedom may increase the likelihood of many bearing children.

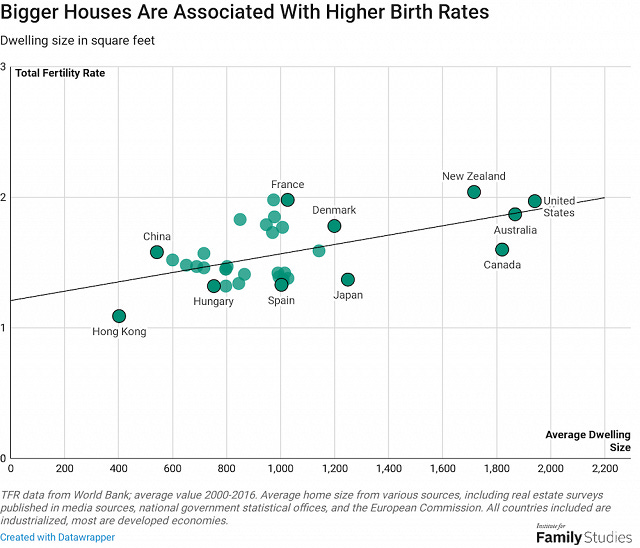

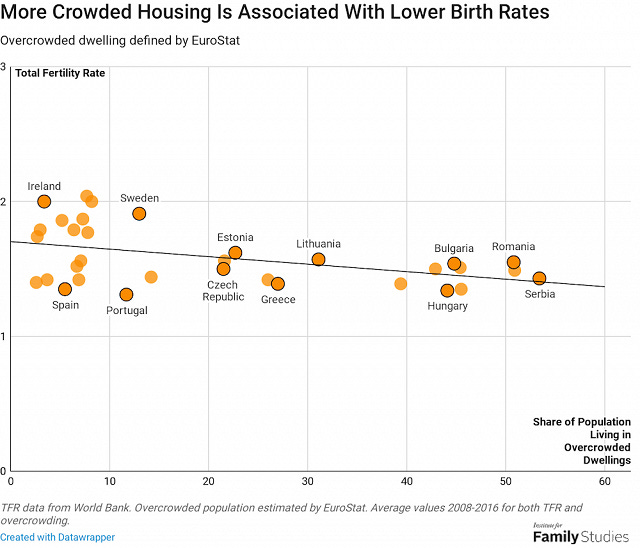

Housing prices

One of the biggest costs of having a child is housing, after all, kids take space! If young people are confined to smaller homes than in the past, or forced to live in more unstable or expensive housing situations, they are unlikely to reproduce. There is some good suggestive evidence that this may be happening already. For example, the real estate company Zillow published a short blog several months ago showing that places with faster home price increases had a faster decline in birth rates.

Houses are considered affordable if median prices are no more than three times median salaries. In England and Wales, in 2022, the median annual earnings for someone on a full-time salary was £33,400. This would mean an affordable home would be around £100,000. Instead, the median price of a housing unit was £270,000. This situation is considerably worse in London and the South East of the country. The problem is also not just confined to house prices and would-be-buyers, private rents are also seriously unaffordable relative to earnings.

The affordability crisis in the UK has hit the younger generation the hardest. For decades, the home-ownership rate has been increasing steadily for over 65-year-olds. However, home-ownership among the 25- to 34-year-olds peaked during the late 1970s, and it fell by half from 1989 to 2016. The number of adults living with parents in England and Wales rose by 700,000 in a decade to 4.9 million.

Unfortunately, reforms that would be effective are considered politically infeasible, and policies that are popular are ineffective or, worse: counterproductive. Fixing the housing crisis will be the most challenging policy prescription on this list, mainly because so many external factors are riding against it (foreign buyers, strict planning laws, apathy within the government, etc.). This does not mean that it’s impossible, however. Below, I have listed a few steps the UK government can take to alleviate this complicated and politically tenuous issue.

A fresh approach is needed that includes building more homes in high-demand areas of the UK, such as the major cities. The National Housing Federation, which represents housing associations across England, suggests new skills and methods of construction could help in future. “This includes building homes in factories out of materials such as timber frames, and then assembling them on site over only a few days,” the NHF says. “Such methods enable homes to be built more cheaply, to a higher standard and more quickly.” Incorporating 3D-printing technology could also be a way forward, allowing small cabins and bungalows to be build in a matter of days. While the technology is still in its infancy, government backing can speed the process up and make it more widely available. The NHF says research from the National Audit Office has suggested that if modern methods of construction are used instead of traditional bricks and mortar, it could be possible to build up to four times as many homes with the same amount of on-site labour.

Research for the National Housing Federation and Crisis, that was conducted by Heriot-Watt University, argued that 145,000 affordable homes should be built annually for the next five years, of which 90,000 a year should be for social rent. This is the lowest-cost housing that councils and housing associations provide, with rents tied to local incomes. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation, says the rules around the right to buy should be changed, so that councils get to keep all of the money raised from sales.

Loosening the number of planning restrictions and making it easier for builders will make supply more elastic. This could involve reducing the amount of protected greenbelt land. It could also involve streamlining the regulations home-builders have to meet.

Many tenancy agreements last six months, or a year, and after that households can be asked to move on. This makes it difficult for people to put down roots and for families to plan for schooling, and generally means an extra cost for renters who have to arrange a move. There are also problems around rental deposits, with tenants asked to find a down payment before they have money back from their existing landlords. The National Residential Landlords Association says as part of the forthcoming renters’ reform bill “the government should develop either a financial bridging facility or a deposit builder Isa to make it easier for tenants to move home without needing to find money for a fresh deposit each time”.

The NRLA is also calling for tenants to get more help to use existing rules that allow them to challenge rent increases they believe to be unfair in tribunals.

Landlords can get interest-only mortgages, which puts them at an advantage over owner-occupiers. Furthermore, council tax bears little relation to a property’s value, meaning a wealthy household can pay the same tax on a home with three spare bedrooms as a family of four crammed into a two-bedroom flat. These policies incentivise investors to put as much money into property as they can get their hands on, pushing up prices. A solution to this would be to overhaul property taxes and mortgages to discourage property speculation. This could also involve higher rates of tax on second homes to disincentivize owning second homes. The government could also step in and prevent foreign businesses and individuals from scooping up large quantities of housing stocks.

In recent years, wage increases have lagged behind house price rises, widening the gap between workers’ annual incomes and the cost of property. To close this gap, governments need to strengthen the social security system, improve employment rights, and continue commitments to increasing the national living wage so it adapts to inflation.

Making cities more-pedestrian friendly and reducing car dependency

When the topic of fertility is brought up, people have a lot to say - quite rightly - on housing prices and maternity leave, but very little attention is actually drawn to the effect the openness of public spaces and cities have on people’s likelihood on bearing children.

Parents, understandably, want their children to grow up in accessible and safe communities. Many feel dissuaded to raise a family in hostile environments, riddled with crime, anti-social behaviour and inaccessible public spaces. Take the average American city, for example. Cars dominate every inch of the city’s area, covering the land in car parks and roads. There are very few public, green spaces or gathering locations for families. And if there are, families are usually forced to traverse by car to reach them. Even if they don’t admit it out loud, this has had a subconscious effect on young couples. Communities began to be viewed as economic centers rather than recreational areas.

While most European countries do not suffer from the same scourge of anti-pedestrianism as American cities, there is still a long way to go before the domination of the car can be weakened. European governments need to encourage and support public transportation and the re-claiming of urban spaces away from cars and highways, just as been done in Amsterdam and Paris, two urban areas speerheading the war of YIMBYism. Opening up the city in this way will make it safer, cheaper and accessible to pedestrians, encouraging more young couples to settle down and raise their own family.

Increasing funding for public transportation, opening up new bike lanes, and cordoning off public spaces for pedestrians are just a few ways governments can achieve this.