Is Trump Engineering A Crash?

The president's weaponisation of tariffs is part of a broader strategy to revive America's industrial base.

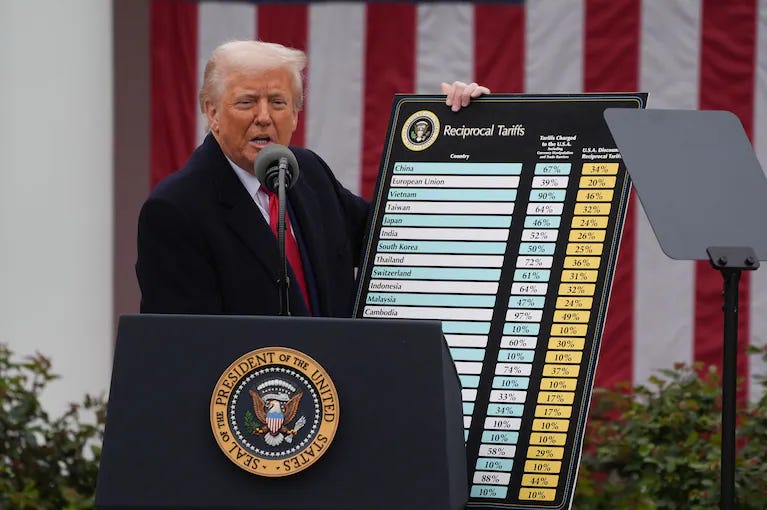

From laptops in South Korea to wine in Italy, from Nike trainers in Vietnam to coffee in Colombia, these array of goods, once a testament to America’s enduring role as a champion of free trade and its standing as the most lucrative market for goods from around the world, are now among the vast categories of goods subject to additional taxes after President Trump, on Wednesday, imposed universal tariffs on all U.S. trade partners. The decision marks a tectonic shift in American trade policy, which has been dominated by a neoliberal consensus since the late 1980s.

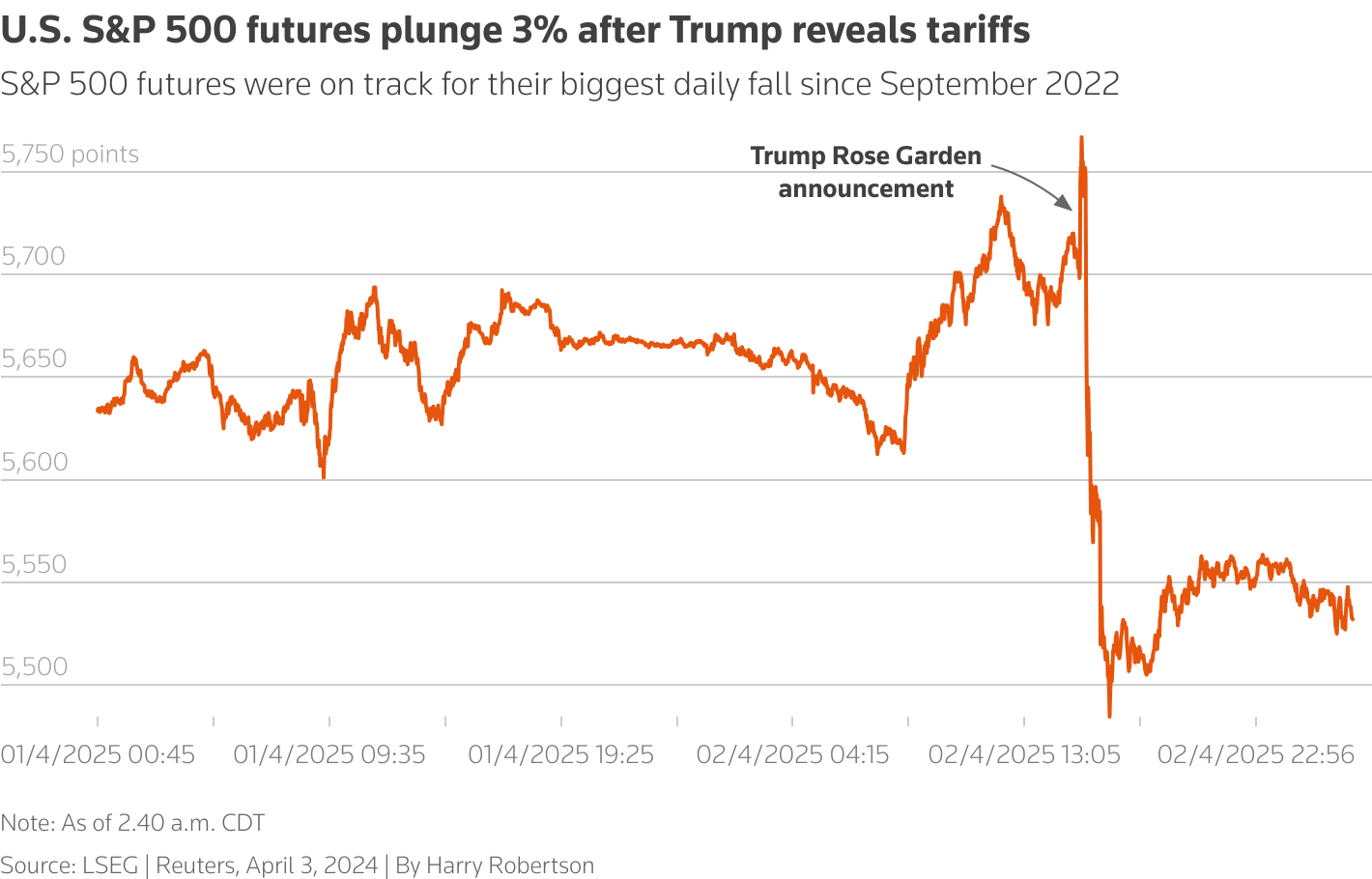

The announcement, hailed by Trump as America’s “Liberation Day,” sent shock waves across the world and raised the specter of a global trade war. Stock markets tumbled on the news, as investors were surprised at the size and scope of the tariffs. Even close allies such as Japan and South Korea were not spared. Neither were countries like Australia and Brazil that buy more from America than they sell to it. It was the latest example of his willingness to take a maximalist position, essentially daring his opponents to take him on.

Allies and adversaries are now scrambling to make sense of Mr. Trump’s tariff barrage. Some threatened to retaliate. Others openly pressed for negotiations, while some quietly pushed for concessions through back channels. Alternatives exist but there will be pain and transaction costs in any diversification.

Protectionist industrial policies are by no means new to American politics. They first saw a resurgence in Trump’s first term when the president levied tariffs against Chinese steel, some of which were kept in place by Joe Biden, who introduced additional levies on Chinese goods such as electric vehicles and solar panels. But the sheer magnitude and scope of these new ‘liberation’ tariffs is unprecedented, offering the fullest repudiation of an embrace of global free trade that began on a bipartisan basis in the 1980s.

Ask any renowned economist whether tariffs will produce economic prosperity and most of them will reply with a resounding no. Conventional theory argues that tariffs raise prices and therefore reduce consumption. In addition to raising prices, tariffs slow economic growth — thus risking stagflation, the bane of every flourishing economy. And, by protecting firms that might not be able to compete with imports, tariffs ensure that a country drifts away from the technological frontier, widening gulfs between its foreign competitors. It’s one of the biggest reasons the global economy embraced free trade in the aftermath of WW2, leading to an explosion in economic development, as middle-class families enjoyed new, cheaper foreign alternatives while developing countries reaped the rewards with new employment opportunities and a chance at modernising their societies.

Not everyone benefited from this exchange, however. In the postwar heyday of American manufacturing nearly 20 million people once made their living from the sector. The United States was a leading producer of motor vehicles, aircraft and steel, and manufacturing accounted for more than a quarter of total employment. Following the drafting of NAFTA in 1994, however, which crystallized this move to a neoliberal economic framework, working-class workers across the Midwest saw their communities dry up as factories were closed down and shifted to Southeast Asia, leading to a decline in the once mighty Rustbelt. As U.S.-based multinational corporations matured, executives and activist shareholders realized that they could often increase production at lower wages overseas, enabling higher profits and reduced prices for domestic consumers. State and federal policymakers, frustrated by testy battles with labor unions in that era of inflation, often supported such adaptations by globalizing firms.

While output and efficiency rose in America when it opened up to China in the Nineties, the gains were largely coalesced by large owners of capital, leaving small businesses and workers behind. Industrial hubs in the American interior have often withered, leaving many strongholds of Mr. Trump’s base on the economic fringes.

An expansive cohort of economists and business leaders remain deeply skeptical of the tariff campaign, however, and of its ability to reverse the decades-long drop in manufacturing employment. Few experts dispute his general diagnosis, however — echoed by a new breed of conservatives, including Vice President JD Vance — that deindustrialization caused a sort of pain that went unnoticed for too long.

President Trump’s imposition of tariffs on a scale unseen in nearly a century is more than a shot across the bow at U.S. trading partners. If kept in place, the import taxes will also launch an economic project of defiant nostalgia: an attempt to reclaim America’s place as a dominant manufacturing power.

It’s too easy to dismiss the decisions taken as the ramblings of a senile, schizophrenic, as our media is so prone to do. There is both an economic and political rationale underpinning Trump’s flirtation with tariffs. They present a chance to rebuild American manufacturing, once the cornerstone of most communities in the Rustbelt, and restore the working class to its former glory. This brings us to a different school of economic theory, one that has found itself a new home in Trump’s orbit. Economists of this kind argue that tariffs can be effectively employed in a strategy to build a country’s industrial base. The classic examples of this are postwar Japan and then South Korea, each of which rebuilt their war-ravaged economies using a combination of state nurturing and protectionism. As a result, they became global manufacturing champions. This is the model Trump’s circle wants to emulate in the hope of spurring a manufacturing renaissance in the country.

It is also a big gamble. Trump thinks - and hopes -that American shoppers are willing to pay higher prices, at least for a while, in exchange for forcing manufacturers to bring jobs back to America. It is a gamble, essentially, that protectionism works, and that the only way to solve the problem is to draw from the lessons of William McKinley, the president Mr. Trump lauded in his inauguration speech. But there are other bets he is taking. He thinks that other nations around the world will reduce tariffs and other barriers to American goods, rather than face the pain. He has argued that tariffs will provide a new revenue stream for the United States, making America less dependent on income taxes.

The fundamental problem is that it’s hard to detect much evidence of strategy in the way Trump is going about it.

For some inexplicable reason, he’s targeting countries that aren’t the source of the US’ problem. the us runs a much bigger trade deficit with China than with Canada but both countries have a similar level of tariffs. Worse, hefty tariffs on Canadian cars won’t actually benefit American carmakers because they’re highly integrated with Canadian firms, meaning that once the tariffs have been implemented, these domestic car manufacturers will be paying for the goods imported, making their products more expensive than imported models from elsewhere.

Trump’s tariffs also lack precision. he’s slapping them on indiscriminately, imposing then suspending them, or announcing carve-outs. Rather than set an economic plan and stick to it, he’s entrenched a reactive policy in which the US will play tariff whack-a-mole with trading partners. It’s hard to parse what advantage the US would gain from raising prices on Colombia coffee, for instance, because the US lacks the capacity to build its own coffee industry due to weather and soil conditions.

Rather than respond to his tariffs by altering their production plans, businesses are starting to stand back, waiting for the fog of war to lift so they can plan better for the future. Knowing the volatility of the president, many seem content enough to just wait and stick to what they’re currently manufacturing and not make big risky moves in case there is another last minute reversal.

Tariffs, when used in moderation and along a coherent strategy can manipulate the market into reducing trade deficits and shifting the demand to domestic goods, reviving national businesses. A good and more recent example to use of tariffs in practice would be the ones the Biden administration imposed on electric vehicles manufactured in China. the reason this was pragmatic was because they were a defined good from one country and were done in tandem with other efforts to substitute demand domestically by subsidizing domestic industries It sought to promote labor union empowerment across all sectors, but especially manufacturing, by backing groups like the United Automobile Workers in old industries and subsidizing new industries like green energy, with made-in-America qualifying provisions.

When applied in Trump’s manner, though, it’s akin to taking a sledgehammer to global markets.

This reveals another apparent flaw in Trump’s approach to this war. Like many declining empires, America is both overestimating its strength and underestimating that of its opponents. The American exceptionalism of recent years, in which its economy has grown strongly while other developed countries have stagnated, was always something of a debt-fuelled illusion. American borrowing has grown at twice the pace of GDP over the last few years. If the US had lived within its means, its economy would be as moribund as its G7 peers.

And where America has been profligate, its trading partners have often been prudent. This has left many of them with ample fiscal firepower to respond to Trump’s provocations. Germany, China and the EU have all announced major increases in spending to stimulate their economies. This will help soften the impact of tariffs and further encourage investors to return home and chase the higher returns on offer.

One theory is that this is all part of a plan — that Trump is deliberately engineering a downturn to squeeze excesses out of the economy before teeing up a strong rebound once his tax cuts and deregulation kick off. It would be a pugnacious approach to economic revitalization, especially since he didn’t ask for a mandate from voters to do this. But it is at least plausible, since that’s essentially what Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan once did. Still, it’s hard to square this fine-tuned strategy with the volatility of Trumpian policy-making. Besides, the tax cuts being proposed are largely baked in, being not new but an extension of the 2017 tax cuts. It’s not clear how much added stimulus they’d bring.

Whatever happens, this much is certain: the backlash from foreign countries will likely be severe and risks plunging the US into a brutal trade war where consumer prices can be expected to rise sharply, undermining one of the key pillars of Trump’s mandate to tackle inflation. But it could also trigger a global realignment that leads to a new chapter in global trade and economic theory, one where the allure of cheaper products takes a back seat for reviving domestic industries.