Legalizing Drugs Should Not Be A Radical Idea

Fifty years since its inception, the War on Drugs has resulted in a colossal failure; it's time the UK shifted its strategy towards drug consumption.

To most people, seeing the words ‘legalizing’ and ‘drugs’ in the same sentence elicits a knee-jerk reaction. It’s considered a great taboo, a red line not worth crossing. And it’s no exaggeration to suggest that this reactionary and, relatively, narrow-minded approach has dictated the last forty years of UK drug policy, a period characterized by missed targets and a booming drug trade.

Fifty years since its inception, the War on Drugs has resulted in a colossal failure. Arresting and incarcerating tens of thousands of people has filled prisons and destroyed lives and families, without reducing the availability of illicit drugs or the power of criminal organizations.

A Brief History

The War on Drugs, first coined by President Nixon at the apex of a national crime wave, crystallised itself in the UK through the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act, an attempt by the then-incumbent Heath government to bring UK drug policy in line with that of the Americans’. This statutory instrument, deemed insignificant at the time, would have repercussions for the country over the next fifty years, manifesting in a heavy-handed approach that has prevented steps towards reform, and cultivated a breeding ground for drug abuse and gangsterism that flourishes in a thriving black market economy.

Instead of responding to the endemic as how it is - a serious failing in our social fabric - politicians treated it almost like civil warfare, a disease that could only be confronted by force. Gone was the empathetic, scientific approach that had influenced British drug policy for decades, replaced by a brutal and unforgiving crackdown that pushed vulnerable addicts further into the shadows, away from oversight and into the embrace of the drug cartels.

The original aim of removing drug addicts from urban streets, clamping down on drug cartels and reducing escalating overdose deaths has been contorted into a policy of civic failure. By all metrics and available data, the War on Drugs has objectively failed. Drug-related deaths, prevalence of use and the availability of drugs have all skyrocketed in the UK since the current prohibition regime was introduced 50 years ago. One only has to glance at the statistics published since then, which illustrate a much bleaker reading. In 2019 alone, 4,393 people died from drug-related causes, an increase of nearly 600 from the previous year. In the period between 2020 and 2021, there were around 210,000 drug offences recorded by the police in England and Wales, 19% higher than what was recorded between 2019 and 2020. The volume of confiscated cocaine has increased by more than 650 times since the 1970s, to 4,274 kg in 2019, making the UK the capital of cocaine use in Europe.

Instead of cutting down on drug consumption and overdose deaths, as originally envisioned, the inverse has occurred. Steve Rolles, a senior policy analyst for the Transform Drug Policy Foundation, aptly summarised it: “Despite the untold billions spent, it has utterly failed in its goals to reduce use and health harms, but has criminalised millions and fuelled a dangerous illegal trade here and around the world.”

A New Approach

The reason the war failed is because addiction was treated as something that could be solved through brute force. Politicians mistakenly believed that by harassing, degrading and punishing drug users, they could put a stop to their vices. But all it did was strengthen a cycle of hopelessness.

In light of these harrowing statistics, a new approach is needed. Maintaining this regime not only fails the many victims but perpetuates a cycle of addiction and exploitation that will continue to tear at our social fabric. In its place, the UK’s new strategy should focus on decriminalization strategies, grounded in science, health, security and human rights.

Before progress on this front can be achieved, however, a major reset will be needed in not just our drug policy, but how wider society discusses and debates the topic. So far, the media and most major institutions remain staunchly opposed to even the notion of debating a change in strategy, which has had the effect of entrenching these unproductive, reactionary views. Challenging these archaic stereotypes will be of the utmost paramountcy before steps can be taken.

By legalizing drugs, we can deprive the cartels of their revenue streams and shift it towards the government. Revenue generated through the distribution of drugs can then be pumped into rehabilitation schemes, with the intention of weaning drug addicts off of their supply. While it will be a slow process and require a lot of patience, by emphasising with drug addicts, and treating it like what it is, an addiction, the government can start to lead these people away from their destructive lifes.

More importantly, by selling the drugs in a safe, controlled environment, like a pharmacy or a clinic, the government can successfully target the primary factors behind these high fatality rates. Most overdose deaths stem from a lack of education surrounding dosages or unclean needles. By bringing drug addicts back into the light, we can help them identify the correct dosage and supply them with clean needles, significantly reducing the number of overdose deaths.

Portugal, A Case Study

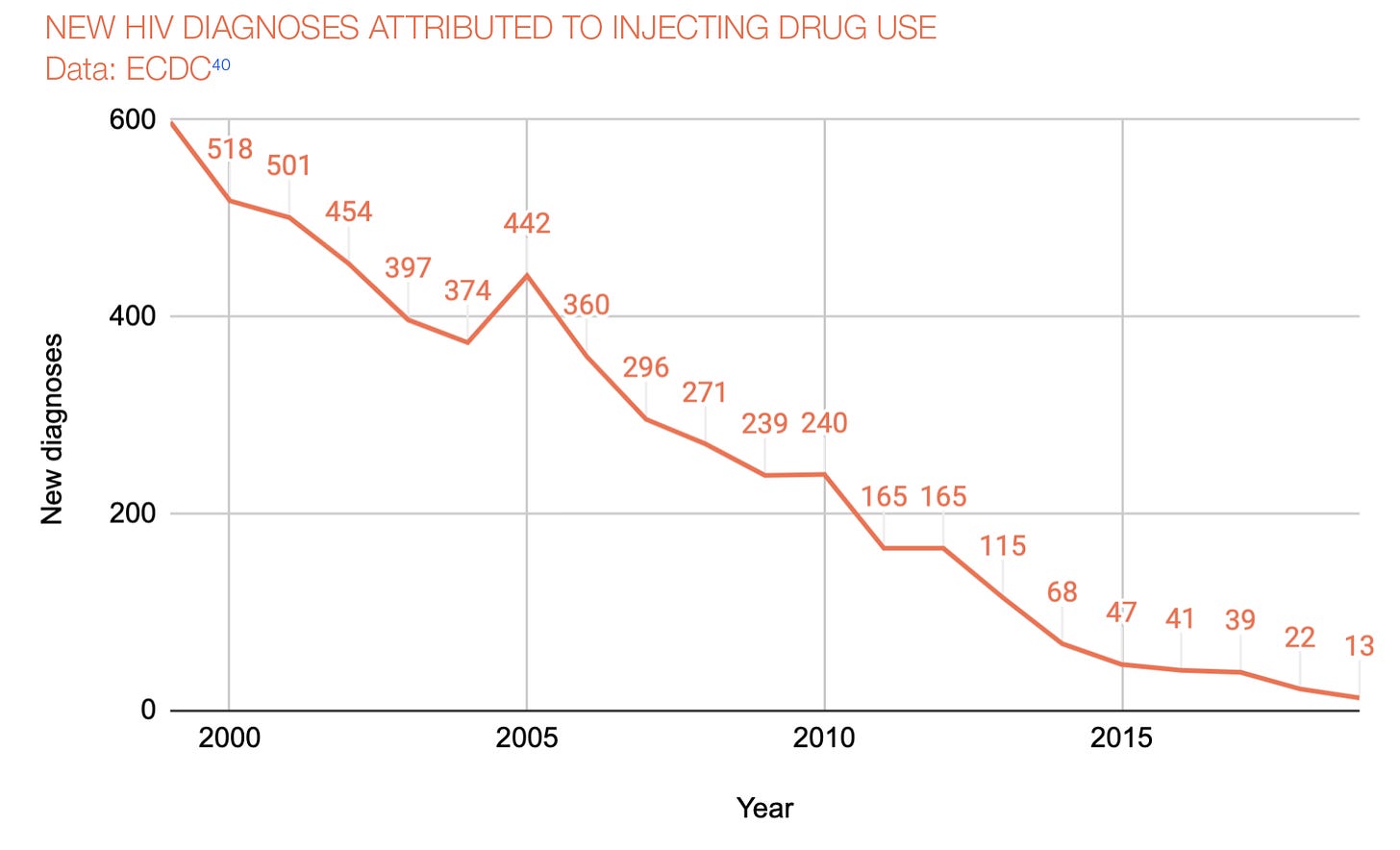

Graph 1: HIV diagnoses related to drug use in Portugal since the decriminalization regime was introduced.

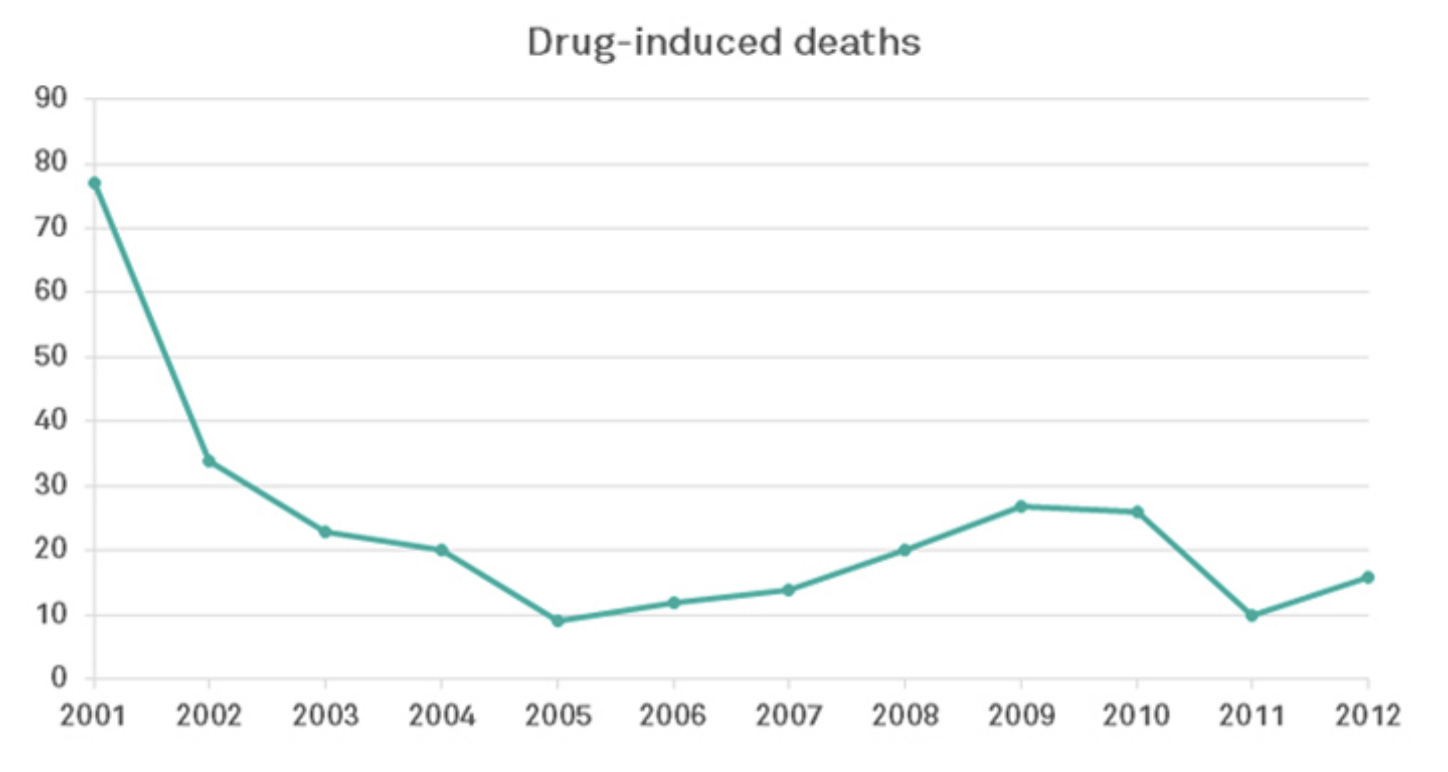

Graph 2: Drug-induced deaths in Portugal, from 2001 until 2012

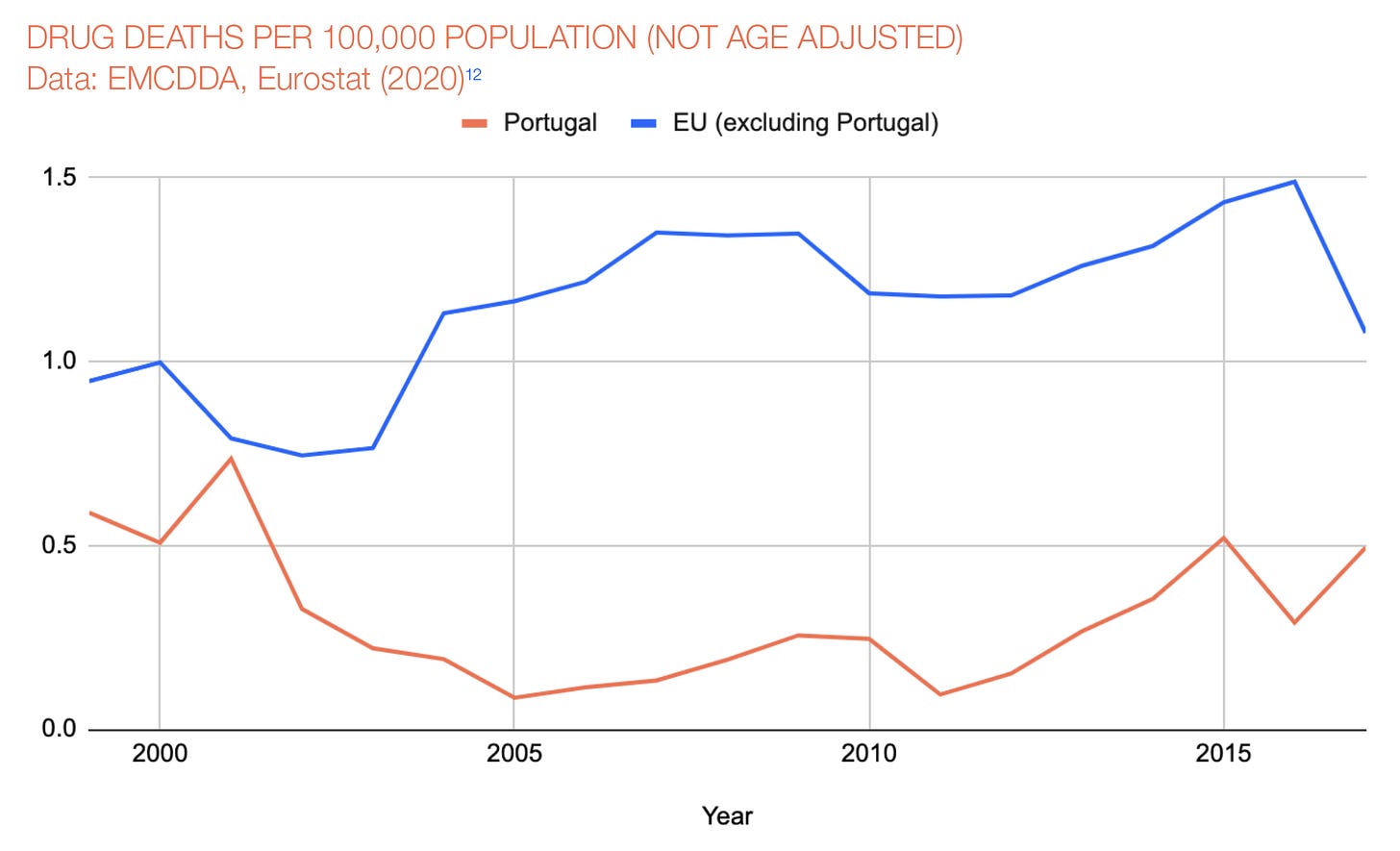

Graph 3: Comparing drug-related deaths per capita between Portugal and EU average; there is a noticeable decline for Portugal’s graph in 2001 when the decriminalization regime was introduced.

Portugal, the only Western country to universally legalize drug consumption, already offers a framework to work towards. In 2001, as part of the country’s strategy to reduce the number of HIV/AIDS cases, the incumbent Socialist government engineered a multi-layered decriminalization program. Harm reduction efforts were expanded, a major information campaign was mounted for the public, and treatment facilities and easier access to substitution treatment for drug addicts were established.

Since then, all signs point to a broad reduction in overdose deaths and consumption rates. New HIV diagnoses amongst drug users fell by 17%, and a general drop of 90% in drug-related HIV infections was recorded in the period from 2001 to 2020. There was an increased uptake of treatment - roughly 60% - as of 2012. The number of drug-related deaths in Portugal reduced from 131 in 2001 to 20 in 2008. As of 2014, Portugal's drug death toll sat at 3 per million, in comparison to the EU average of 17.3 per million, one of the lowest drug-related death rates in the EU and the developed world. And, while there was a noticeable increase in drug consumption during the recorded period, the increase in drug use observed among adults in Portugal was not greater than that seen in nearby countries that did not alter their drug laws. Finally, it is estimated that the social cost of drug use (the sum of public expenditure on drugs, the private cost incurred by the addict and costs taken inflicted on society) decreased by 12% on average in the 5-year period following the establishment of NSAFD in 1999, and an 18% on average reduction since 2010.’

Similar drops in problematic drug use, especially heroin, were observed in both Switzerland and the Netherlands after adopting policies that emphasized treatment rather than criminalization.

A New Future

It is abundantly clear that the status quo cannot continue, and it seems that the country is, slowly, starting to crave a new sense of direction. William Hague, former leader of the Conservative Party and Foreign Secretary, a man not known for his moderate views, published an article in The Times in 2021 calling on the government to follow Portugal’s lead and chart out a new course in its drug policy. These calls for reform were echoed by the SNP government in Scotland, which has begun considering steps to legalize Scotland’s drug laws.

While this level of enthusiasm is yet to be translated to the general public - with a YouGov poll from 2022 finding that seven in ten Britons (70%) still think that the possession of hard drugs should be a criminal offence - there has been a noticeable shift away from the inflammatory rhetoric that defined the panic-driven years of the 1980s and 1990s, towards a more conciliatory and facts-driven consensus in recent years.

Still, there is a long way to go yet. Only by championing this reforming crusade at every opportunity and highlighting the positive developments of a legalization programme to the people can progress start to be made. Once the general public begins to become more receptive to the idea of a decriminalization regime, then, logic dictates, politicians will fall under pressure to steer UK drug policy away from its current destructive path and towards a future where addicts are not forced to suffer in isolation. When that happens, the UK can finally close a bleak chapter in its history.