The UK Is A Dying Nation

From crumbling schools to high NHS waiting lists, stagnant growth to low wages, Britain is a nation in decline. Forty years of neoliberal economics combined with a haughty elite have held the UK back.

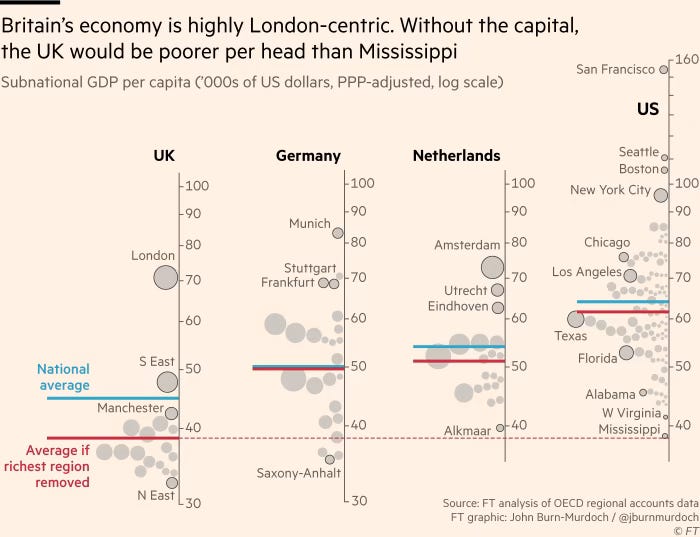

To fully understand the extent of hopelessness and despair permeating modern Britain, one only needs to glance at the graph above.

Published in the Financial Times a few months ago, the study highlights the economic disparity between selected regions in several Western nations. Germany, America and the Netherlands were shown to be relatively equal - if the wealthiest region was subtracted from the overall equation, the overall GDP per capita of those countries would not change dramatically, reflecting a proportionate distribution of wealth across the country.

The same could not be said of the UK. Removing London not only saw the UK’s average per capita drop substantially but also brought it to parity with Mississippi - by every metric, the most deprived state in America.

Though it may appear simplistic on the surface, hidden behind that facade of blue and red lines and grey blobs of varying magnitude, lies a deeper picture, one entrenched in history. The graph, so simple in its presentation, perfectly highlights the economic woes of a country castrated by its own elite for the last forty years.

When discussing an issue as multifaceted as a country’s decline, there is no simple answer or single party to blame - it is an amalgamation of several, often conflicting, factors that have intersected over the years to herald the destitution, humiliation and impoverishment of the British people and their land. The purpose of this new series is to disentangle this confusing web, outlining the factors behind this decline, explaining why they came into fruition and, perhaps, offering ways in which it can be halted, if not reversed.

In part one of this series, I’ll be taking a brief look at Nimbyism and the role it plays in perpetuating Britain’s chronic under-investment.

HS2, Infrastructure and the Scourge of NIMBYISM

After studying the recent decline in British prosperity, one fact becomes strikingly clear: the country's political elite is devoid of ambition. Avant-garde ideas are immediately met with either disdain or distrust, with adherence to the same fundamentally broken orthodoxy maintained.

Such myopic attitudes have been detrimental to the country’s future, jettisoning economic growth and perpetuating local decline. Regional inequalities, already some of the worst in the developed world, are producing major differences in living standards, education and life expectancy. There are many factors behind this, of course, but the biggest is under-investment, as developers are cowered from investing resources into projects that are unlikely to manifest.

It has been almost thirty years since Britain built a nuclear power station. More than thirty years since we last built a reservoir. As a country, we are living off the legacy of infrastructure investments made decades ago. This isn’t sustainable.

Local opposition to infrastructure remains paramount in the UK’s political discourse. Wherever you go, one cannot escape the ubiquitous nature of NIMBYism, which permeates every layer of government, from parish councils to local planning boards to the parliament in Westminster. Regardless of their duties or influence, they are all united by an anti-growth agenda, an inherent hostility to development.

By blocking the construction of new homes, grid connections, factories, film studios, wind turbines, solar farms, nuclear power stations, data centres, laboratories, rail links, and roads our planning system hammers economic growth at every turn. And without economic growth, everything else gets much harder.

Instinctively dismissing the concerns raised by locals would be counterproductive, as there are a few legitimate grievances to want to curtail rapid expansionist plans. No one wants to see developers bulldozing over pristine, natural land and erecting dull, grey tower blocks. Nor do they want building developers desecrating an ancient Anglo-Saxon burial site unearthed somewhere.

However, when one moves past these sympathetic objections, the entrenched NIMBY agenda becomes more trite, asinine and farcical. Instead of making reasonable demands, local institutions, clinging to their last semblance of relevancy, lash out at any incursions on public land, often justifying their resistance with contrived

Take, for instance, Britain’s film industry, which has become a national success story. Demand for studio space continues to out-strip supply. In fact, estate agents Knight Frank estimate Britain will need an additional 2.6m sq ft of studio space to keep up with demand.

Yet, planning permission has been refused for a scheme to build a new £750m state-of-the-art film studio on the site of an old quarry next to the A404. Despite backing from big-name directors James Cameron, Sam Mendes, and Paul Greengrass, plus a commitment to invest £20m into the local road network, the project was rejected by Buckinghamshire Council. Joy Morrissey, the local MP, told a local paper that she was ‘delighted’ by the news.

And it isn’t just £750m film studios that you can’t build on disused quarries next to major roads in Buckinghamshire either. The same council rejected the construction of a £2.5bn data centre on another quarry near the M25. One of the reasons cited for rejecting the project, which would have created 370 jobs and helped the UK’s burgeoning AI sector, was that the buildings could be seen from nearby motorway bridges. That was not the only massive investment in data centres to be refused recently. A £1bn investment in a new data centre next to the M25 near Watford was blocked by Three Rivers council.

This anti-growth vision manifests itself in various forms across the country. When preservation societies oppose extensions and councils fail to meet house-building targets, families are forced to live in small, cramped flats, housing stock is badly maintained, and, worst of all, children are penned into flats inundated with chronic mold.

But the most egregious manifestation has, undoubtedly, been through HS2. First announced in 2009 at a cost of £37.5bn, the high-speed railway, designed to cut commute times between Birmingham and London, the two largest cities in the UK, from 1hr and 21 minutes to 51 minutes, has been beset by delays and cost re-evaluations, mostly as a result of local opposition and the UK’s archaic planning laws. Now, the project’s price tag rests at an eye-watering £98bn and the second leg, which would have extended to Manchester and Leeds, has been scrapped.

In contrast, Spain - a country with a significantly lower population, GDP and a larger, more varied topography compared to the UK - has built 2,500 miles of high-speed railway in the last 30 years. Through a combination of unusual political consensus and robust, government funding, Spain has built one of the most enviable public transport systems in Europe, if not the world. This remarkable achievement offers a blueprint for the UK to follow. It is a transformation that has fundamentally changed people’s lives. Trains are increasingly the fastest and cheapest way to travel around the country. More than 300 high-speed trains operate daily. And they are almost always on time. (If a Renfe high-speed train is delayed by more than 15 minutes, you get a 50% refund of the cost of your ticket. If the delay exceeds 30 minutes, you get a full refund).

The productivity of sectors like life sciences, AI, and film depends upon what we’ve built. It’s not just that you need labs and film studios to have a life sciences sector or a film industry, though admittedly it helps. It is also about where your labs and your film studios are. One of the reasons why Marlow quarry was an attractive place to invest £750m in a film studio is that it is near lots of other film studios.

The fluidity of labour mobility offered by such a fast, cheap, reliable public transportation system would be nothing short of emancipatory, allowing goods and workers to move more easily across the country, and distributing the wealth currently trapped in London across the other urban centres, which have languished in the absence of industries brought on by globalism.

There’s no reason why the UK cannot emulate this success story. As the fifth largest economy in the world, boasting some of the most renowned engineers globally, the only factor holding these types of infrastructure back is the entrenched nature of NIMBYISM and the cowardice of Westminster to challenge it.

Enough Talk, Solutions

If it wants to climb out of this widening gulf, Britain needs to shift the focus of its education system towards STEM subjects, fund new infrastructure and transport projects, support R&D clusters. But, more importantly, it must improve the elasticity of labour mobility. One way it can achieve this is by updating Britain’s archaic planning laws.

Planning reform is a controversial topic, but it’s also a source of credibility on what is traditionally a weakness for Labour: the economy. Crucially, given the tough fiscal environment, unlike the plan to spend £15bn a year on the green transition, planning reform doesn’t cost the exchequer anything.

An easy solution would be to reduce the stakes of a judicial review. When legal challenges succeed, the costs can be enormous. Essentially forcing developers to begin the process all over again. Losing a legal challenge on one small aspect shouldn’t send a project back to the drawing board. Rather, permissions should stay granted conditional on resolving that specific problem. This would get spades in the ground faster and discourage the use of legal challenges as a delaying tactic.

Additionally, the British government needs to tackle over-consultation. While consultations can help pre-empt community objections and improve designs, it can also overburden developers with unnecessary bureaucracy, raising costs and delaying time. In theory, only a single short consultation is required but developers do more in fear that their consultations will be found to be inadequate and challenged in the courts. So, perhaps it would be worthwhile to take a leaf out of France’s book and create a British equivalent of the Commission nationale du débat public, essentially a public body that sets extremely clear guidance on what is and isn’t needed for adequate consultation? The approach should be ‘consult well, consult once’.

In summary, Britain desperately needs to get building again. Whoever wins the election must get this right, otherwise we’re looking at another decade of lost potential.