Trump's 2024 Campaign: A Masterclass In How To Fumble An Easy Election

Whatever happens on November 5th, one thing is abundantly clear: Trump has run his worst campaign yet. And it might cost him an election which once looked like it was in his grasp.

‘Does Donald Trump actually want to win this election?’ That’s the question I’ve found myself asking over the past month as I’ve watched his campaign stumble across the country, swaying from one scandal to the next, lacking any sense of momentum or direction, almost like a drunken sailor.

It’s hard to believe it was only a few months ago that he had emerged unscathed from an attempted assassination plot, raising and pumping a clenched fist to his rabid crowd of supporters as a streak of blood ran down his ear, as he shouted ‘fight back’ triumphantly. It was a moment that looked like it might be written into the annals of history, the moment it seemed like a second Trump term was inevitable. Now, with less than a week to go until American voters elect their next president, it’s nothing but a fleeting memory, a snapshot to a different time when Trump’s opponent was the ailing Biden and not the more energetic and affable Harris. Voters rarely bring up the assassination when prompted while only the most zealous Trump supporters can flaunt it on memorabilia for a quick buck to sell.

Perhaps, this speaks to the lack of impetus guiding his campaign this time around. If you follow politics long enough, you’ll start to understand that campaigns are won and broken on narratives and the candidate that can set the debate on which the election is run on is usually - though, not always - in the strongest position to win outright.

Trump is fully aware of this. In fact, he wielded that tool very effectively in his first national race. In 2016, he capitalised on anti-establishment sentiment by positioning himself as the political outsider, ready to rip down the corrupt establishment by challenging Hillary Clinton, the living embodiment of the political elite, which had ignored post-industrial towns in the Midwest. In doing so, he expanded the Republican voter coalition to include Rustbelt working-class White voters, a demographic which had been one of the Democratic Party’s most faithful supporters since FDR’s New Deal. Michigan, a state which hadn’t voted for a Republican since 1988, flipped to the GOP’s column, marking a paradigm shift in American politics only someone like Trump could bring about in the modern era.

Then, four years later, in 2020, Trump, like the chameleon he is, shifted his approach, styling himself as the trusted and responsible Commander-In-Chief, who could lead America through the pandemic and into the unknown world on the other side. He regularly contrasted himself, , rather successfully, with the Democratic-run cities of Chicago, Portland and Minneapolis, which were, at the time, swarmed by anti-police protestors and burning to the ground as racial grievances placed Democratic leaders in an awkward position. And he almost won. Only 44,000 votes dispersed over three crucial swing states stood in his way to re-election.

Now, he finds himself grappling an identity crisis, one of his own creation. While ours may be an age of polarisation, a rare zone of consensus in American politics is the admission that the Trump campaign has been self-sabotaging itself with a series of unenforced errors, some of which may prove fatal enough to deny him a second term.

On paper, this election should be a resoundingly easy for the former president to win. All of the conditions, both political and economical, are there, ready to propel him back to the White House. There’s an anti-incumbency bias sweeping across the world, as voters remain disillusioned with governments at the stagnant economic growth following Covid and the stubbornness of global supply chains to readjust. On Oct. 27, Japan’s long-ruling conservative Liberal Democratic Party suffered one of its worst electoral results. Over the summer, after being in power for 14 years, Britain’s Conservative Party collapsed in a landslide defeat, and France’s ruling centrist alliance lost over a third of its parliamentary seats. And current polling suggests the trend of losses is overwhelmingly likely to continue when Canadians go to the polls next year for a vote that Justin Trudeau’s Liberals are on track to lose by an overwhelming margin.

Which is just to say that almost everywhere you look in the world of affluent democracies, the exact same thing is happening: The incumbent party is losing and often losing quite badly. There is simply no example of an incumbent party in a rich country securing a strong re-election.

It appears that the unhappy electorates are unhappy in fundamentally the same way. Inflation spiked, largely because household spending patterns seesawed so abruptly during and after a global pandemic, and though it’s been tamed, prices of many goods have not fallen to what voters remember, and what’s more, the process of taming has involved higher interest rates, which in their own way raise the cost of living. The question of why, exactly, voters so hate inflation — which increases wages and prices symmetrically — has long puzzled economists. But the basic psychology seems to be: their pay increase reflects their hard work and talent, while the higher prices are the direct fault of the government.

Voters have also shifted noticeably to the right on certain issues like immigration and crime, all of which are historically fertile ground for Republican candidates. A majority of American voters say that the country is heading in the wrong direction and desire change.

Yet, for some unexplained reason, he keeps throwing obstacle after obstacle in his own path. Conversely, it’s also palpably true that the things liberals believe should be costing Trump support — the events before and around Jan. 6, the rollback of abortion rights, his tendency to ramble incoherently — have, in fact, hurt him. Some of this comes down to Mr. Trump’s personality, his scandals and his association with the overturn of Roe v. Wade. But he has also waged a very strange campaign for a candidate receiving a boost from voters’ concern with inflation.

First, when Biden withdrew from the race and Harris became the presumptive nominee, there was a small window in time for the Trump campaign to set the narrative by painting his new opponent in a different light, putting her on the defensive and supplying himself with ammunition to further wreck her image with. How did he spend that time? By attacking her style of laughter and fixating on her mixed heritage. Who that message was expected to resonate with, that’s anyone’s guess, but it proved to be a good early sign for how incoherent and disorganised his campaign would end up being.

In the final week of a presidential election campaign, the Republican candidate’s message is derailed by the remarks of a speaker at a partisan gathering. The speaker makes an inflammatory statement that offends a key voter demographic; in the end, it is enough to cost the Republicans a crucial swing state and hand the election to the Democrats.

This may very well end up as the story of the 2024 election, but it is actually a description of an election that took place 140 years ago: the race of 1884, which saw GOP frontrunner James G. Blaine felled by the infamous remark of Rev. Samuel Burchard, who described the Democrats as the party of “rum, Romanism, and rebellion”. The demographic in question were Irish Catholics who, angered by Burchard’s insult, turned New York State blue by the slimmest of margins. Grover Cleveland consequently became the first Democratic president since the Civil War.

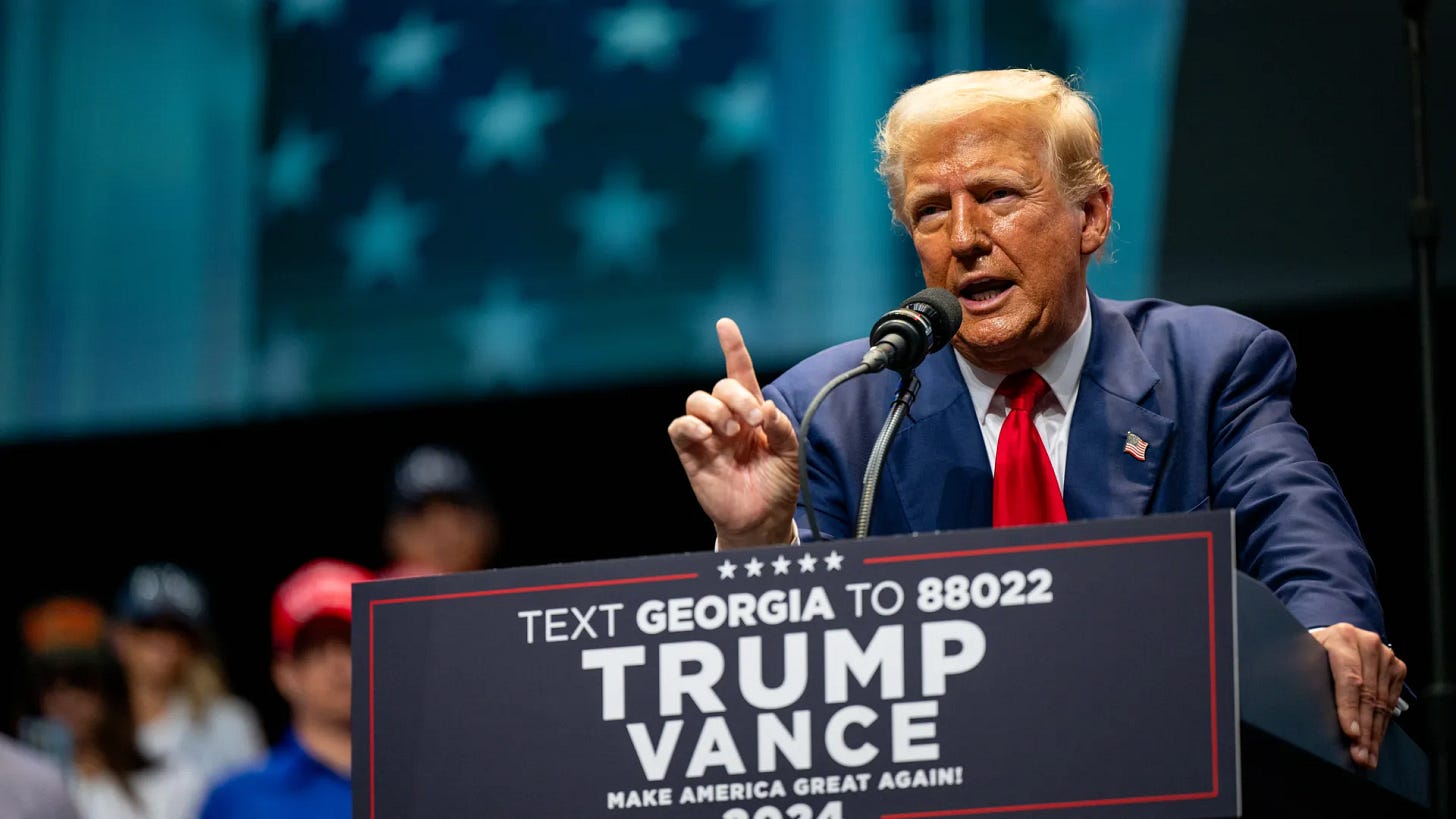

In 2024, Republicans face an eerily similar scenario. At a Donald Trump rally at a sold-out Madison Square Garden in New York, comedian Tony Hinchcliffe called Puerto Rico a “floating island of garbage in the middle of the ocean”. Puerto Rico is, of course, an unincorporated territory whose inhabitants are American citizens.

The fallout was swift and far-reaching. In must-win Pennsylvania, where nearly 5% of the population are of Puerto Rican heritage, Spanish-language radio stations and informal social media amplified Hinchcliffe’s joke among the local Borinquen community. A non-partisan civil society group, the National Puerto Rican Agenda, published an open letter urging the community not to vote for Trump, while Puerto Rican rapper Bad Bunny promptly endorsed Kamala Harris (his endorsement has previously moved the needle in the election for Puerto Rico’s governor).

The trouble for Republicans is that this joke which, in any other context, might have been waved away as a tasteless attempt at shock humour, now risks stalling or even undoing the ongoing movement of Borinquen and Latino voters toward the GOP, fuelled by the growing alignment on socially conservative values and working-class identity, which has been years in the making. Hispanics account for a growing percentage of the American electorate and are a vital voting block in many swing states, especially Nevada, Arizona and Pennsylvania. To Trump’s relief, perhaps, the Latino community is not a monolith. What offends Puerto Ricans will likely have very little impact on people with separate Latin American ancestry. But it could still make a few question their votes and in a race which will be decided by razor-thin margins, every vote is valuable.

In the final stretch of the campaign, Trump has chosen the soldily blue states of New Mexico and Virginia (both of which hasn’t voted for a Republican since 2004) to make his final pitch to voters. It’s a baffling decision that poetically summarises the state of the campaign and ironically mirrors the strategic blunders made the Clinton campaign back in 2016 when they reduced operations in Wisconsin and Michigan.

Sure, the election is still not over. Tens of millions of Americans are still yet to vote. A not-so-insignificant amount remain undecided. Republicans are, surprisingly, leading Democrats in early voting in states such as Nevada and Arizona. A Harris win and a Trump loss is not inevitable. But that doesn’t mean the signs don’t look bleak for the GOP. If Trump does, in fact, win in November, it will be in spite of his campaign, not because of it. And if Republicans do lose, it may strike them that they squandered what should have been an astoundingly winnable election.